#8

As promised, it’s time to talk about the dreaded dream sequence. It’s almost as cliched as the “split personality” trope or the infamous “hero was actually the killer.” That said, all of these tropes can be done right. Major spoilers as always.

Clearly I’m not opposed to dream sequences, as I did review ten different versions of A Christmas Carol last year. I think the Christmas Past scenes in A Christmas Carol 1951 work particularly well, even though they are technically flashbacks as well. The distant finale in Raising Arizona closes a goofy and hilarious film on a surprisingly poignant note, while the short nightmare scenes of Angel Heart amp up the creepy atmosphere even more. I’ll give credit where credit is due that a lot of the best dream sequences actually come from The Sopranos, because they actually feel like dreams, but seeing as how that’s TV, it’s a tale for a different time. For my #8 slot, I’ve chosen the lengthy dream sequence at the end of Spike Lee’s 25th Hour.

After a day of mentally and physically preparing himself for his seven-year prison sentence, Monty Brogan (Edward Norton) gets picked up by his father James (Brian Cox). Monty has been beaten up at his request by Frank (Barry Pepper) so he’ll look tough in prison, and the beating may have gone a little overboard. On the way to prison, James offers his son freedom. He says that at Monty’s word, he’ll drive west and let his son start a new life.

James imagines having his first drink in two years with Monty before he says goodbye for good. Monty starts a new life with a new identity, and eventually he even reunites with his girlfriend Naturelle (Rosario Dawson) and starts a family. We know it’s a fantasy sequence, but as it goes on and on, we start to forget, perhaps willingly. We want Monty to run away and start this new life, living the American dream in a small town somewhere. Monty is a criminal, yes (drug dealer), but we still want the best for him.

Color is used wonderfully in 25th Hour, but unlike the multicolored night life of New York, the colors here are incredibly muted. The images subtly get brighter and more blurred as they go on, feeling more and more distant and out of Monty’s reach.

It’s a standard happy ending, but as Monty’s future family grows old together, we cut back to the car. They’re still on the way to prison. We knew it was a dream, but it still hurts to be pulled out of it. When we are, we realize Monty isn’t awake. I suppose it’s up for interpretation, but I’ve always felt the dream sequence is his father’s and not his. James narrates the whole thing, and it’s sort of a cliched Hollywood version of what he would want for his son. James hasn’t had the perfect life he dreams up for his son, and he would clearly give everything for his son to be happy, even if it means breaking the law.

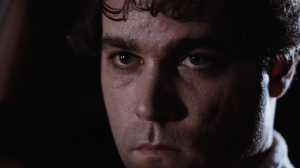

Then the film ends on a close-up of Monty’s horribly bruised face, the car shaking him around a bit.

Is this meant to call to mind a child being driven somewhere by this father? Is Monty finally at peace? Or did Frank attack him too hard and he’s dead? Spike Lee dares not tell us everything, just ending the movie here. It’s a brilliant way to finish an incredibly rule-breaking movie.

Tomorrow, I’m going to take a look at the funniest movie scene of all time.